Fire the bureaucrats and break the Left’s grip on education—or keep losing.

Showdown or Surrender

There’s no separate peace with our centralized elites.

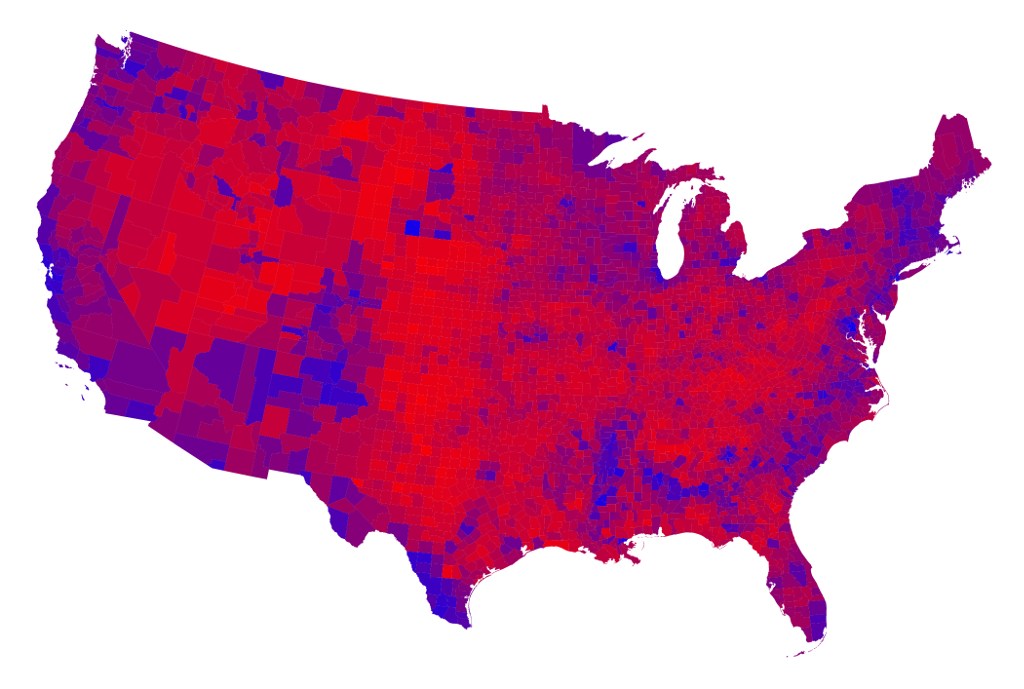

Looking at a map of blue Democratic states and red Republican states, it is easy to fall into the trap of concluding that the U.S. is divided along geographic lines into separate societies. On the basis of this assumption, Democrats during Republican administrations and Republicans during Democratic administrations often revive old theories of states’ rights to defend their constituencies from the other party. But this is a potentially fatal prescription based on a mistaken diagnosis. The consequence of placing false hopes in federalism could be ceding power by default to the national managerial overclass.

For most of American history, the Mason-Dixon line was the major division in political geography. From the 1800s until the late 20th century, there was a Southern elite party allied with much of the Northern white working class—the Jeffersonian Republicans to the Roosevelt-Johnson Democrats. And for two centuries there was a Northern elite party—the Federalists, Whigs, and Lincoln-to-Eisenhower Republicans—based in New England and the upper Midwest, which sometimes found allies among alienated white Southern hill country populists and championed the rights of black Southerners, on the realist principle that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

There is no longer a Southern gentry with values and lifestyles and dialect that are distinct from those of the old Northeastern patrician elite. The former regional oligarchies have fused into a single homogeneous national overclass, mostly hereditary but partly meritocratic. Its geographically mobile, careerist members attend the same selective private and public universities, speak the same homogenized non-regional elite dialect, read the same newspapers and ‘zines, watch the same TV shows and movies, follow the same fashions and have the same diets.

There are no red and blue states. The most accurate maps of voting are county maps, not state maps. And the county maps show that the major partisan division, in every region of the U.S., is between urban cores and everywhere else. Outside of densely populated metro areas, California is red. Most metro areas in Texas are blue. Because cities and counties are mere creations of state governments, the moment that politicians representing a slight majority of statewide voters capture power in state government they can use that power to overrule local governments everywhere in the state. This means that, once a majority of voters in a few large metropolitan areas capture a state legislature and governor’s office, there may be no way for their exurban and small-town rivals to fight back.

Describing this as an “urban-rural” divide is wrong. Only 1.3% of American workers actually work on farms. The major divide everywhere is within metro areas: between downtown business districts and inner suburbs, on the one hand, and outer suburbs and exurbs, on the other.

The New Class Geography

Does this partisan divide reflect different societies, each of which could exist apart from the other? No. It reflects different classes as well as different racial and religious groups within the same highly centralized, deeply integrated society. The populations of hub cities in the U.S., as in Europe, tend to include the mostly-white, college-credentialed economic elite in business, finance, the professions, the academy, media, and government, and a largely-immigrant working class that labors for them for low wages in menial service jobs. While some commute from the outer ring to the urban cores, most working-class Americans of all races live and commute and work in the suburbs and exurbs. In addition to providing low-prestige services like fast food and discount retail, mostly to each other, the exurban working class works in logistics, infrastructure, manufacturing, energy, agribusiness and other “dirty” productive industries exiled from the hub cities of the overclass.

Think of today’s highly nationalized and urbanized U.S. as the United City-State of America. Imagine putting all of the blue hub city cores—the downtowns and inner suburbs of New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Austin, Atlanta—together in a single big blue circle. Then imagine putting all of the exurbs of the same cities together in a much larger red ring around the blue inner circle, with a checkerboard pattern of contested suburbs.

This imaginary diagram illustrates the new reality that modern American national politics is essentially New York-style urban politics, replicated everywhere. All of the hub city cores are the equivalent of Manhattan today, and all of the peripheries are the equivalent of New York City’s outer boroughs. This explains why nobody thought it odd that both presidential candidates in 2016 were New Yorkers. And it explains why a contributor to National Review’s Never Trump issue in 2016 mocked Trump’s “outer borough accent.”

The newly consolidated national managerial and professional overclass is still divided among the two parties, although it is becoming more Democratic in partisanship, now that the Democrats are the party of the college-educated and of the most politically influential U.S. industries, Silicon Valley and Wall Street. But whether they are Clinton-Obama-Biden Democrats or Bush-Romney-Ryan-Haley Republicans, the hub-city oligarchs tend to share the same public philosophy of woke neoliberalism—moderately progressive on cultural and social issues, while economically center-Right, in favor of the free market when it comes to trade, immigration, regulation of tech and finance and hostility to private sector unions (as distinct from public sector unions, part of the Democratic coalition). In each party, the donors and managers and professionals have far more in common with those of the other party—in terms of education, lifestyle, and values—than they do with most of their own party’s non-elite voters, whom party elites manipulate with various “culture war” issues—cost-free gestures of affirmative action tokenism on the Left, insincere rhetoric about outlawing abortion on the Right.

The consolidation of almost all political, social, and economic power in a single national ruling class whose members congregate in a few major cities is unprecedented in American history, though not in the history of Latin America or France or Britain. The new geography of class has two implications for champions of the non-elite working-class majority of Americans and their few overclass allies today.

Nationalism or Nothing

First, given the decline of churches and private-sector labor unions and membership-based rather than donor-based political parties, the only remaining national institution in which high-school-educated working-class Americans have any influence at all is the government. By means of their vote, ordinary people still have some partial influence over government, however diluted it may be by the influence of donors and the college-educated elite.

In contrast, the national overclass, in addition to controlling most but not all of the government, has unchecked domination of the private sector, including the media, and the nonprofit sector, including the universities and major philanthropic foundations. If the elite fails to persuade the electorate to vote for race and gender quotas in democratic referendums like California’s failed Proposition 16, then the elite will use private commercial power instead of government power to impose them, as NASDAQ has done by imposing race and gender quotas on the boards of corporations that it will list—quotas which will be filled by elite white women, as well as members of minority-group elites.

From this it follows that smaller-government conservatism is inimical to the interests of the working-class majority of all races, whose champions need to increase their power in the only institution they influence, the government, and wield it aggressively on behalf of ordinary Americans to check the abuses of concentrated private power of oligarchs in business, media, and the nonprofit and academic sectors.

Second, the battle must be for control of the federal government and the institutions of national government power. It is a delusion to believe that a hostile national elite, in charge of the national government, will nevertheless allow dissenters and enemies to shelter behind states’ rights or localism. In the United States of 1820, when states’ rights protected Northern antislavery activists against the Southern slaveholders who controlled federal offices most of the time in that era, defensive localism might have been possible. In 2020 defensive localism is anachronistic.

Anti-government conservatism is not the answer to the threat posed to the values and interests of America’s transracial working-class majority by overclass control of all sectors, including the private sector and the nonprofit sector. On the contrary, mindless anti-statism threatens to throw away the only instrument available to the American working-class majority for defending its values and interests against the ongoing managerial revolution from above—democratic government.

In the centralized United City-State of America, the inhabitants of the outer boroughs cannot secede. They have no choice but to fight to control city hall or lose by default.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Our moralizing modern-day aristocrats are at odds with American justice.

A proposal for a renewed America.

Donald Trump and the Altogether True and Amazing Origin of the United American Counties.